How Rasputin Inspired the “Fictitious Persons” Disclaimer Commonly Seen in Movies

“This is a work of fiction,” declares the disclaimer we’ve all noticed during the end credits of movies. “Any similarity to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events, is purely coincidental.” In most cases, this may seem so trivial that it hardly merits a mention, but the very same disclaimer also rolls up after pictures very clearly intended to represent actual events or persons, living or dead. Most of us would write it all off as one more absurdity created by the elaborate pantomime of American legal culture, but a closer look at its history reveals a much more intriguing origin.

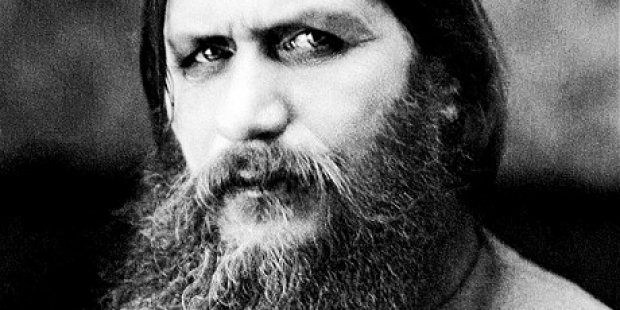

As told in the Cheddar video above, the story begins with Rasputin and the Empress, a 1932 Hollywood movie about the titular real-life mystic and his involvement with the court of Nicholas II, the last emperor of Russia. Having been killed in 1916, Rasputin himself wasn’t around to get litigious about his villainous portrayal (by no less a performer than Lionel Barrymore, incidentally, acting alongside his siblings John and Ethel as the prince and czarina). It was actually one of Rasputin’s surviving killers, an exiled aristocrat named Felix Yusupov, who sued MGM, accusing them of defaming his wife, Princess Irina Yusupov, in the form of the character Princess Natasha.

The film casts Princess Natasha as a supporter of Rasputin, writes Slate’s Duncan Fyfe, “but the mystic, wary of her husband, hypnotizes and rapes her, rendering Natasha — by his logic, with which she agrees — unfit to be a wife. Yusupov contended that as viewers would equate Chegodieff with Yusupov, so would they link Natasha with Irina,” though in reality Irina and Rasputin never even met. In an English court, “the jury found in her favor, awarding her £25,000, or about $125,000. MGM had to take the film out of circulation for decades and purge the offending scene for all time,” though a small piece of it remains in Rasputin and the Empress’ original trailer.

Things might have gone in MGM’s favor had the film not included a title card announcing that “a few of the characters are still alive — the rest met death by violence.” The studio was advised that they’d have done well to declare the exact opposite, a practice soon implemented across Hollywood. It didn’t take long for the movies to start having fun with it, introducing jokey variations on the soon-familiar boilerplate. Less than a decade after Rasputin and the Empress, one nonsensical musical comedy previously featured here on Open Culture) opened with the disclaimer that “any similarity between HELLZAPOPPIN’ and a motion picture is purely coincidental” — a tradition more recently upheld by South Park.

via Kottke

Related content:

The Romanovs’ Last Ball Brought to Life in Color Photographs (1903)

Watch an 8‑Part Film Adaptation of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina Free Online

Watch the Hugely Ambitious Soviet Film Adaptation of War and Peace Free Online (1966–67)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.