JWST won’t find the very first stars, but a new telescope can | by Ethan Siegel | Starts With A Bang! | Jun, 2025

Many were hoping that JWST would find the first stars of all. Despite many hopeful claims, it hasn’t, and probably can’t. Here’s how we can.

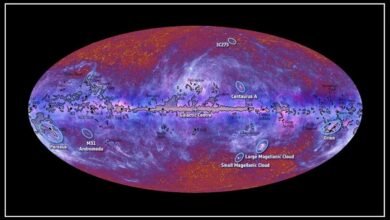

It was only three short years ago that we still lived in the Hubble era, with the most distant object then discovered being galaxy GN-z11, whose now-arriving light was emitted just 420 million years after the Big Bang. In July of 2022, however, JWST began science operations, and in just a few short months, there was a new cosmic record-holder, as its larger aperture, colder temperatures, and longer wavelength sensitivity allowed it to find objects that were invisible to a telescope like Hubble. As of the end of May, 2025, GN-z11 is now just the 14th most distant galaxy known, with the light from current record-holder MoM-z14 coming from just 280 million years after the Big Bang, or 140 million years earlier than GN-z11.

And yet, despite all our best endeavors to find them, any signature of the first stars remains elusive. We know that, immediately after the start of the hot Big Bang, there were no stars or galaxies; it takes at least many millions of years for gravity to pull matter together in sufficient densities to trigger the ignition of nuclear fusion. We’ve searched for…