The British War on Slavery

In August of 1833 the British passed legislation abolishing slavery within the British Empire and putting more than 800,000 enslaved Africans on the path to freedom. To make this possible, the British government paid a huge sum, £20 million or about 5% of GDP at the time, to compensate/bribe the slaveowners into accepting the deal. In inflation adjusted terms this is about £2.5 billion today (2025) but relative to GDP the British spent an equivalent of about $170 billion to free the slaves, a very large expenditure.

Indeed, the expenditure was so large that the money was borrowed and the final payments on the debt were not made until 2015. When in 2015 a tweet from the British Treasury revealed this surprising fact, there was a paroxysm of outrage as if slaveholders were still being paid off. I see the compensation in much more positive terms.

Of course, in an ideal world, compensation would have been paid to the slaves, not the slaveowners. Every man has a property in his own person and it was the slaves who had had their property stolen. In an ideal world, however, slavery would never have happened. Thus, the question the British abolitionists faced is not what happens in an ideal world but how do we get from where we are to a better world? Compensating the slaveowners was the only practical and peaceful way to get to a better world. As the great abolitionist William Wilberforce said on his deathbed “Thank God that I should have lived to witness a day in which England is willing to give twenty millions sterling for the abolition of slavery!”

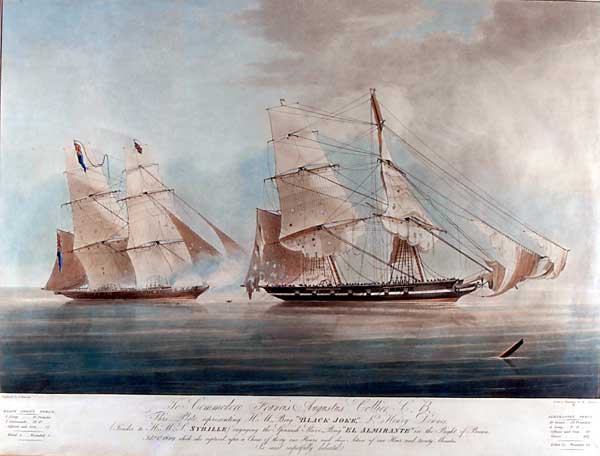

The 1833 Slavery Abolition Act was preceded by the 1807 Slave Trade Act which had banned trade in slaves. In an excellent new paper, The long campaign: Britain’s fight to end the slave trade, economist historians Yi Jie Gwee and Hui Ren Tan assemble new archival data to assess how the Royal Navy’s anti slave-trade patrols expanded over time, how effective they were at curtailing the trade, the influence of supply-side enforcement versus demand-side changes on ending the trade, and why Britain persisted with this costly campaign.

Britain’s naval suppression campaign began on a modest scale but the campaign grew in strength throughout the 19th century, peaking in the late 1840s to early 1850s when over 14% of the entire Royal Navy fleet was deployed to anti-slavery patrols. The British patrols captured some 1,600 ships and freed some 150,000 people destined for slavery but they were at best only modestly successful at reducing the slave trade. The big impact came when Brazil, the largest remaining market for enslaved labor (by the mid-19th century, nearly 80% of trans-Atlantic slave voyages sailed under Brazilian or Portuguese flags), enacted its anti slave-trade law in 1850. Britain’s campaign was not without influence on the demand side however as passage of the Aberdeen Act in 1845 allowed the Royal Navy to seize Brazilian slave ships and that put pressure on Brazil and helped spur the 1850 law.

The suppression patrols were expensive (consuming ships, men, and funds), and Britain derived no direct economic benefit from them. Yet, even during the Napoleonic Wars, the Opium Wars, and the Crimean War, the Royal Navy continued to station ships, even high-tech steam ships, off West Africa to catch slavers. Due to the expense, the patrols were controversial and there were attempts to end them. Gwee and Tan look at the votes on ending the patrols and find that ideology was the dominant factor explaining support for the patrols, that is a principled opposition to the slave trade and a belief in the moral cause of abolition kept Britain in the war against slavery even at considerable expense.

Ordinarily, I teach politics without romance and look for interest as an explanation of political action and while I don’t doubt that doing good and doing well were correlated, even during abolition, I also agree with Gwee and Tan that the British war on slavery was primarily driven by ideology and moral principle as both the compensation plan and the support of the anti-slavery patrols attest.

British taxpayers shouldered an enormous military and financial burden to eliminate slavery, reflecting a generosity of spirit and a sincere attempt to address a moral wrong—an act of atonement that stands as one of the most unusual and significant in history.

The post The British War on Slavery appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.